Introduction: The Critical Role of Dairy Animal Nutrition and Feeding Strategies

The successful operation of a modern dairy farm is fundamentally dependent on the strategic and precise feeding of dairy animals. In today’s high-stakes environment, nutrition is no longer a matter of simply filling the feed bunk; it is a sophisticated, data-driven discipline that directly dictates the economic viability and long-term sustainability of the herd. Optimal dairy cow feed management is the lever that controls everything from daily milk volume and milk component quality (fat and protein) to reproductive success and the cow’s overall lifespan.

Thank you for reading. Don't forget to subscribe & share!

An improperly balanced ration is an expensive proposition, translating directly into reduced efficiency, increased incidence of costly metabolic diseases (like ketosis and milk fever), and diminished fertility. Conversely, a finely tuned, stage-specific feeding strategy is the most effective way to maximize milk yield through precise nutrition and ensure a high ROI (Return on Investment) from every animal. This guide provides a deep dive into the foundational nutrients, advanced feed management techniques, and critical lifecycle strategies necessary for elite dairy performance.

II. Fundamental Nutritional Requirements and Ration Components (H2: Key Dairy Feed Nutrients)

A well-formulated dairy ration requires balancing six core nutrient classes, ensuring that both the cow and her resident rumen microbes are adequately nourished.

A. Water: The Most Essential Nutrient

Water is the cheapest and most crucial nutrient, yet it is often the most overlooked. Water comprises approximately 87% of milk, and restricted water intake immediately halts feed consumption and subsequently reduces milk output. A lactating cow requires 3 to 5 pounds of water for every pound of milk produced, plus maintenance needs. Dairy animal feed management must prioritize access to clean, fresh, and temperature-appropriate water (ideally 40–65°F). Trough cleanliness and monitoring water delivery systems are critical aspects of maximizing dry matter intake (DMI).

B. Energy and Calorie Sources in Dairy Cow Rations

Energy fuels lactation, locomotion, reproduction, and maintenance. The industry standard for measuring energy is Net Energy for Lactation (NEL), which is derived from the Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN) content of the feed. The objective is to provide a dense, highly digestible source of energy that minimizes the risk of digestive upset.

Strategic use of common energy feeds includes starches from ground or steam-flaked grains (corn, barley) and fermentable fibers from high-quality corn silage or beet pulp.

The goal in ration balancing is to provide a mix of fast-releasing energy (starches) and slower-releasing energy (fiber) to ensure a steady supply of volatile fatty acids (VFAs)—the cow’s primary energy source—while maintaining a stable rumen pH.

C. Protein Requirements for Dairy Cattle

Protein is complex due to the unique microbial ecosystem within the rumen. The protein provided must satisfy both the needs of the rumen bacteria (Microbial Crude Protein, or MCP) and the cow’s tissue requirements.

Balancing Rumen Degradable Protein (RDP) vs. Rumen Undegradable Protein (RUP): RDP is fermented by the microbes, creating MCP, which is then utilized by the cow. RUP (or “bypass protein”) escapes microbial degradation and is digested directly in the small intestine, providing the host cow with essential protein for milk synthesis and body maintenance. An optimal ratio (usually 60-65% RDP, 35-40% RUP) ensures efficient nitrogen utilization.

Amino Acid Balancing: After RUP and MCP are digested, the resultant amino acids dictate milk component production. Methionine and Lysine are often the two most limiting amino acids in dairy rations. Supplementing with specific, protected forms of these amino acids is a common strategy in high-producing herds to boost milk protein percentage.

D. Maintaining Rumen Health: The Critical Role of Fiber in Dairy Diets

Fiber is indispensable for the health of the rumen and is measured using two key metrics:

Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF): Represents the total fiber (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin). Intake is often limited by the NDF content of the diet, as it creates fill.

Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF): Represents the least digestible part (cellulose and lignin). High ADF content indicates a lower-quality feed.

Effective Fiber (eNDF) and SARA Prevention: The physical characteristics of fiber, known as eNDF, are critical. Long, coarse forage particles stimulate chewing (cud-chewing), which generates large volumes of saliva, a natural buffer rich in bicarbonate. Insufficient eNDF or diets too rich in rapidly fermentable carbohydrates can cause the rumen pH to drop below 5.5, leading to Sub-Acute Ruminal Acidosis (SARA)—a major culprit in depressed milk fat test and laminitis.

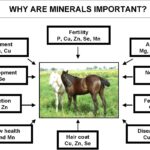

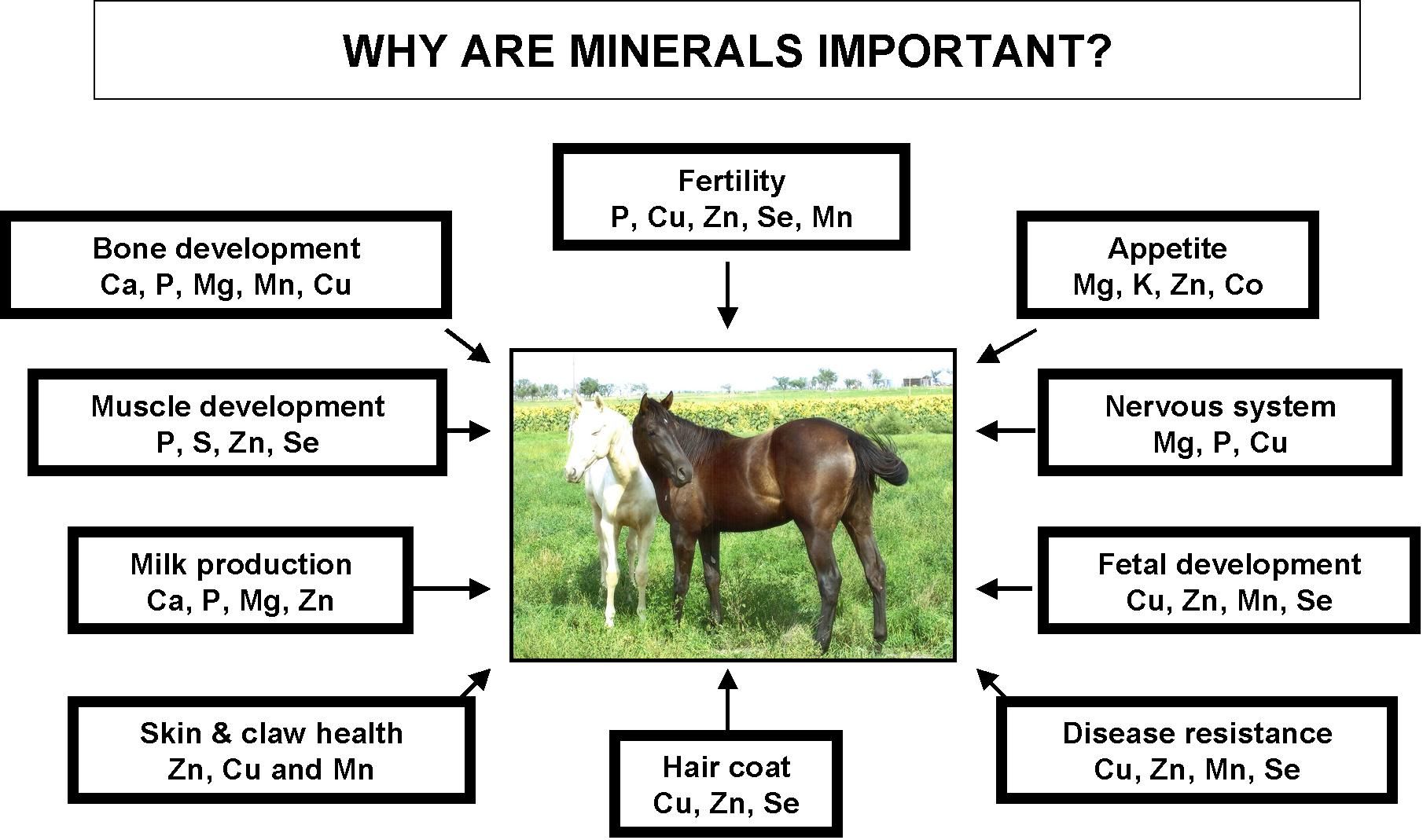

E. Essential Minerals and Vitamins

These micronutrients support metabolic processes, skeletal integrity, and immunity.

Macrominerals (Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Potassium, Sodium, Sulfur) are needed in gram quantities. For instance, Calcium and Phosphorus are integral to milk production, while a carefully managed balance of Potassium and Sulfur is essential during the dry period.

Microminerals (Trace Minerals like Copper, Zinc, Selenium) function as cofactors for enzymes that drive immune response and antioxidant activity.

Vitamins (especially A, D, and E) are crucial for vision, bone health, and immune function, respectively.

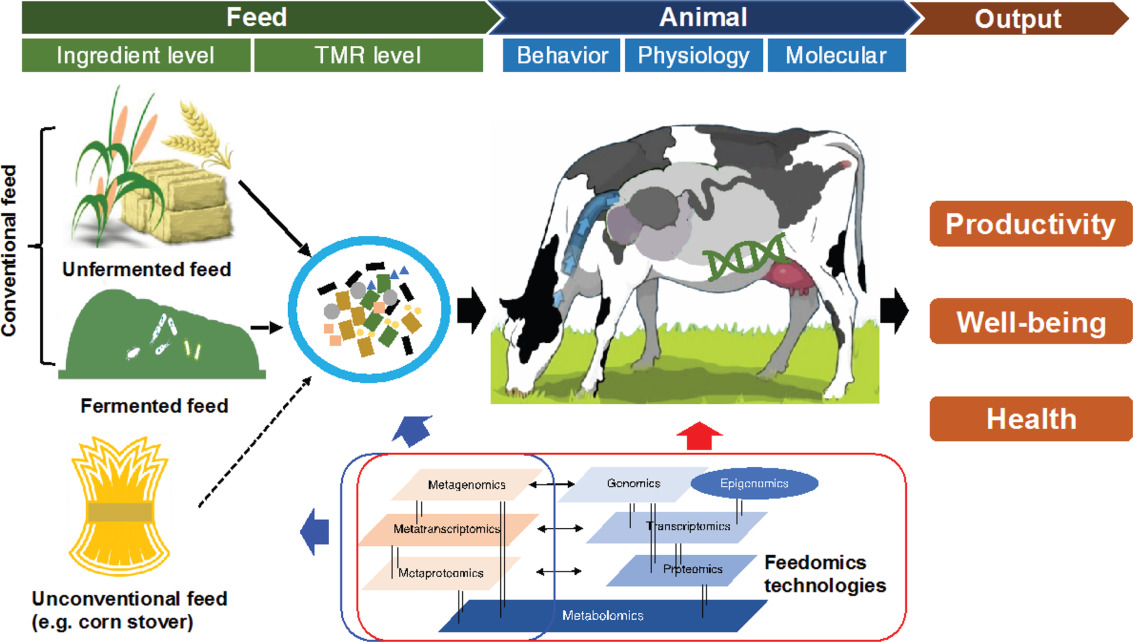

III. Major Feed Types, Quality, and Strategic Utilization (H2: Dairy Feed Ingredient Management)

The strategic sourcing, preparation, and quality control of feed ingredients separate the top-tier dairies from the rest.

A. Forage Quality and Harvesting

Forages should constitute at least 40–50% of the total ration DMI. Their quality is often the most variable and most impactful factor.

Corn Silage Management: Success depends on the right harvest moisture (typically 32–38% DMI) and particle size. Proper packing to eliminate oxygen and effective inoculation are necessary for rapid, controlled fermentation, resulting in a stable, palatable feed.

Hay and Haylage Assessment: High-quality alfalfa or grass hay is crucial. Nutritionists utilize Relative Feed Value (RFV) and Relative Forage Quality (RFQ) to benchmark and price hay based on its potential intake and digestibility.

Pasture Utilization: While cost-effective, integrating managed rotational grazing strategies requires frequent paddock rotation and careful monitoring of grass height and density to ensure consistent nutrient delivery.

B. Concentrates, Grains, and High-Energy Supplements

Concentrates elevate the nutrient density of the diet, supporting high yields.

Grain Processing Methods: Processing is crucial for starch utilization. Steam flaking or fine grinding of corn maximizes digestibility in the small intestine, providing more glucose for lactose (milk sugar) synthesis, which drives milk volume.

Specialized Supplements: Rumen buffers (like sodium bicarbonate) help stabilize rumen pH. Protected fats are used as a high-density, low-fill energy source, especially during early lactation, without interfering with fiber digestion. Yeast cultures are common additives used to stimulate microbial activity and oxygen scavenging in the rumen.

C. Economic Feed Alternatives: Strategic Use of Dairy By-Products

To manage volatile feed costs, many managers safely incorporate by-product feeds. These include distillers grains, brewers grains, cottonseed, and soy hulls. While often economical, their nutritional composition can vary widely between loads and sources. Consistent feed testing is mandatory to ensure the chosen ration remains accurately balanced, preventing unexpected drops in production.